Victor

There are an estimated 57,700 people in modern slavery in the US according to GSI estimates. The US attracts migrants and refugees who are particularly at risk of vulnerability to human trafficking. Trafficking victims often responding to fraudulent offers of employment in the US migrate willingly and are subsequently subjected to conditions of involuntary servitude in industries such as forced labour and commercial sexual exploitation. Victor travelled to the US on a work visa where he thought he would be able to get a better life. However, upon arrival his employer took all his documents and subjected him to verbal and physical abuse. In this narrative Victor talks of the importance of speaking out and asking for help.

Artem

The UK National Crime Agency estimates 3,309 potential victims of human trafficking came into contact with the State or an NGO in 2014. The latest government statistics derived from the UK National Referral Mechanism in 2014 reveal 2,340 potential victims of trafficking from 96 countries of origin, of whom 61 percent were female and 29 percent were children. Of those identified through the NRM, the majority were adults classified as victims of sexual exploitation followed by adults exploited in the domestic service sector and other types of labour exploitation. The largest proportion of victims was from Albania, followed by Nigeria, Vietnam, Romania and Slovakia. In 2009 Artem, a 56-year-old Hungarian, was working as a builder and bus driver. The recession left him unemployed, homeless, and supporting his elderly mother. Duped by false promises he came to the UK. He was forced to live in a small house with 25 men, working 70 hours per week for £10. He escaped, living in disused garages but was re-trafficked twice and was too afraid to leave for fear of becoming homeless again. Artem was found by police after a failed suicide attempt. He was identified as a victim of human trafficking and moved to safe accommodation in Birmingham in 2014.

Trong

China remains a source, transit and destination country for men, women and children subject to forced labour. There have been a number of media reports exposing cases of forced labour in the country, especially among the disabled whose families are unable to care for them and with an underdeveloped government support system leaving them vulnerable. The disparity of work opportunities between rural and urban populations has created a high migrant population vulnerable to human trafficking. The lure of a higher income leads many migrant workers to accept jobs in China without knowing exactly what they entail. Trong went to China from Vietnam after his aunt told him he could get housework near the border. He was told he would work for a couple of months and then return home. However upon arrival he was told by other Vietnamese workers that he had been deceived. Trong had been enslaved into debt bondage in a brick kiln, forced to work to cover the costs of transportation and accommodation. Eventually Trong along with his friend Lin were able to escape.

Siti

Foreign workers constitute more than 20 percent of the Malaysian workforce and typically migrate voluntarily—often illegally—to Malaysia from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Burma, Indonesia, the Philippines, and other Southeast Asian countries, mostly in pursuit of better economic opportunities. Some of these migrants are subjected to forced labour or debt bondage by their employers, employment agents, or informal labour recruiters when they are unable to pay the fees for recruitment and associated travel. Siti was 14 years old when her last remaining relative passed away and she needed to earn money. She was approached by a woman who told her she could get her factory work in Malaysia. However, upon arrival in Malaysia Siti was forced to work long hours in various homes doing domestic work. In the five years she was enslaved, Siti did not earn any money and was subjected to physical and sexual abuse. Following a tip off, Siti was finally rescued during a raid operation.

Oleg

Forced labour accounts for 98 percent of cases of modern slavery in Russia. Made up of both Russian and foreign workers, particularly from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan, these people are enslaved in the agricultural and construction sectors, in factories, private homes, forestry, automotive and fishing industries. Russia also stands as the second largest migrant receiving country in the world, these migrant workers often rely on underground networks and intermediaries, not knowing exactly what work they are committing to. Increased unemployment, poverty and demands for cheap labour among Russian citizens, along with the flow of cross-border migration has created new pockets of vulnerability and opportunities for labour exploitation in the country. Wanting to live independently Oleg took a job he found in a newspaper. Oleg was taken from Moscow along with other men to an unknown location. Forced to live and work in unsanitary and dangerous conditions, the men were threatened with violence at any suggestion of resistance. With the help of one of the bus drivers, Oleg was eventually able to escape and make his way back to home.

Lin

China remains a source, transit and destination country for men, women and children subject to forced labour. There have been a number of media reports exposing cases of forced labour in the country, especially among the disabled whose families are unable to care for them and with an underdeveloped government support system leaving them vulnerable. The disparity of work opportunities between rural and urban populations has created a high migrant population vulnerable to human trafficking. The lure of a higher income leads many migrant workers to accept jobs in China without knowing exactly what they entail. Lin travelled to China with his friend Trong from Vietnam when he was told he could get housework near the border. He was told his travel expenses, food and accommodation would be taken care of and he would earn a good salary. However, upon arrival he found himself in debt bondage, forced to work long hours under the threat of violence in a brick kiln to pay off his incurred fees. Eventually Lin was able to escape along with his friend Trong, hiding out in a nearby forest to avoid discovery.

Ismail

Men, women and children make up those trafficked in Indonesia, subjected to forced labour and commercial sexual exploitation. Brokers working in rural areas are known to lure men and boys into forced labour on palm oil, rubber and tobacco plantations. This is often done through debt bondage, in which employers claim the enslaved owes them money for costs that were never agreed upon and as such they must pay off these debts before they can regain their freedom. Threatened with violence and death they become trapped and feel unable to escape the long working hours and heavy labour they must endure without pay. Rising unemployment and slowed job creation has pushed people into the informal sector unprotected by labour laws, and thus has made them more vulnerable to exploitation. There are currently only 18 shelters in Indonesia working to rescue and rehabilitate traffic victims. Unable to afford to continue his education and believing that he could earn more money abroad to support his family, Ismail had been working illegally in Malaysia when he was deported to Dumai, Sumatra where he was approached by a man claiming to be an official. From the moment he departed Dumai Ismail began to accumulate debt, he was told he would be working in the logging industry to pay this off. Subjected to heavy labour under the threat of death, it was only when he was transferred to another workplace with a more lenient boss that Ismail was able to escape and reunite with his family.

Chinaman labourer living at Gaboon, French Congo

Congo state camp at Lukula, Mayumbe country

Repairing bridge over forest swamp, Kasai – Sankuru District

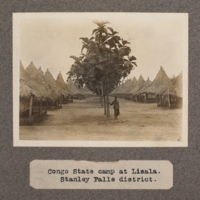

Congo state camp at Lisala. Stanley Falls District

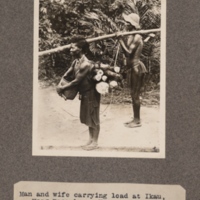

Man and wife carrying load at Ikau, near Basankusu, upper Congo

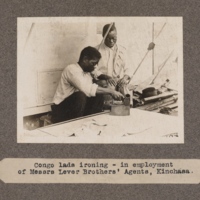

Congo lads ironing – in employment of Messrs. Lever Brothers' Agents, Kinshassa

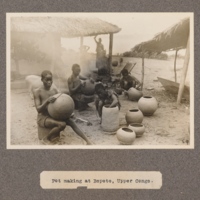

Pot making at Bopoto, upper Congo

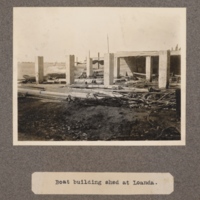

Boat building shed at Loanda

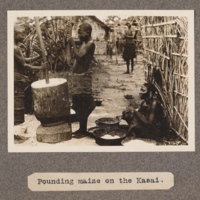

Pounding maize on the Kasai

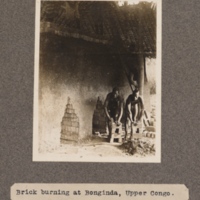

Brick burning at Bonginda, upper Congo

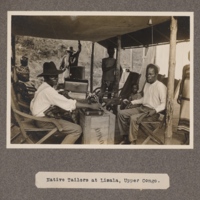

Native tailors at Lisala, upper Congo

Bolobo fishers, with their produce for sale at Leopoldville