Solms Delta

Solms Delta is a wine estate, situated east of Cape Town in the heart of the Cape Winelands. It was founded as Zandvleit in 1690, with the name change coming in 2002 after purchase by University of Cape Town-based neurosurgeon Mark Solms who wished to distinguish it from other farms with the same name. As with the majority of South African wine farms of a similar age, its early labour force rested on enslavement. Solms approach to farm ownership has seen him attempt to eschew the well-worn white owner/black worker relationship by launching a socio-economic reform project. Money has been invested in new housing featuring satellite television, whilst an education project both for workers and their children has been established. Social enrichment activities based around music, sports, and performance have been encouraged in an attempt to improve the traditionally poor socio-economic circumstances of the workers, many of whom live on the estate just as their ancestors did. Solms has explained in interviews that this refreshed approach to wine farming arises from a perceived responsibility to acknowledge his own life privileges as a white South African. Crucially, workers have been given shares in a land equity scheme.

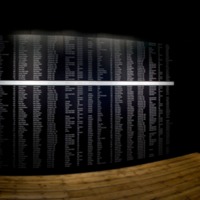

Solms Delta hosts two museums. One of these, named Museum van de Caab with deference to Cape slave naming patterns, opened at the same time as the estate opened to the public in 2005, with a music museum opening in 2014. Acknowledgement of the past as a means of understanding how workers have been exploited over time is a crucial part of Solms’ project. Slavery is referenced in both museums, with songs as evidence of slave culture appearing in the music museum. In Museum van de Caab it forms a fundamental part of a general farm history which traces the story of the land to the origins of humankind. A memorial feature occupies a prominent position in one of two galleries, detailing the names of every person revealed by archival research to have been enslaved on the estate. Guided museum and estate tours are available, conducted by estate workers.

Groot Constantia

Founded in 1685, Groot Constantia is South Africa’s oldest wine estate. Like the majority of wine estates of a similar vintage in the Cape Town area, its labour force prior to emancipation in 1834 rested on enslavement. Following a vine disease outbreak in the late nineteenth century, the estate passed into government ownership. It is currently operated by the arms-length Groot Constantia Trust. The manor house was rebuilt in Cape Dutch style following a fire in 1925, and has operated as a preserved site since that time. The manor house passed into the control of the South African Cultural History Museum in 1969 and, as with other sites managed by the same entity, became part of southern state-funded umbrella Iziko Museums in 1998.

Iziko’s inauguration signalled a shift towards previously marginalised histories at all its sites, with Groot Constantia no different. A revised history of Groot Constantia paying greater attention to enslaved people was written by curator Thijs van der Merwe and published in 1997. Buildings which had potentially served either as stables and/or as slave quarters were repurposed as an Orientation Centre in October 2004. As the first heritage space which the visitor reaches upon arrival, displays in this building foreground the Cloete family – owners from 1779 to 1885 – as ‘farm owners and slave owners’. Drawn from archival research, their human transactions are listed, whilst the origins, names, and worked carried out by people enslaved at Groot Constantia are also listed. A panel is devoted to the ‘young servant boy’ Friday, whose ancestral origins are linked to the suppression of the slave trade by the British Royal Navy. The selection of this story can partially be attributed to the availability of suitable museological material, given that a photograph of Friday carrying Bonnie Cloete’s archery set is included.

National Museum of African American History and Culture

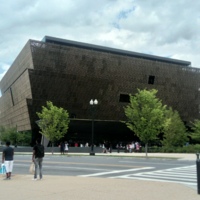

The National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in September 2016, after more than a century of development. Designed to "tell the American story through the lens of African American history and culture," it forms the only national museum in the USA that is exclusively devoted to the documentation of African American history and culture. It stands on Washington's National Mall as the newest, nineteenth museum of the Smithsonian Institute. Established by an Act of Congress in 2003, the museum has had over one million visitors since its opening.

The displays in the museum are divided into two halves. There are three history galleries, charting key events in the history of America, with specific reference to the experience of the African American community. These galleries begin with displays about Africa prior to the slave trade, showcasing the rich culture and advanced nature of civilisations there. The displays then move on to enslavement, the Middle Passage and Plantation Life. In all of these displays, the experience of the enslaved people is central to the interpretation, and much use is made of archive material, providing quotations which bring the voices of the enslaved to the fore of the narrative.

The displays in the history galleries go on to interpret abolition, reconstruction, emancipation and Civil Rights. They end with the inauguration of Barack Obama in 2009. The displays make use of a wealth of collections, some 36,000 objects now belong to the museum. The key to the narrative throughout all of these displays is the central position of African Americans to the national history of America.

The other side of the museum consists of three 'community galleries.' Again these focus on the achievements of African Americans, through themes like sport, military, theatre, television, literature and art. Here, some of the museum's 'celebrity' artefacts, including Michael Jordan's NBA finals jersey and one of Jimi Hendrix's vests. This section of the museum also houses the 'Robert Frederick Smith Explore Your Family History Centre,’ where visitors can look at digitised archive material with expert guidance to explore their own family tree.

Pniel Museum

Pniel Museum is a small community-run museum which opened in 2013 in the village of Pniel, close to Stellenbosch. It has its roots in a long-running project, dating back to the unveiling of the Freedom Monument on the werf area of the former Papier Moelen manor house (which now houses the museum) in 1993. Pniel itself is a former Apostilic Union mission station which was established in 1843. Many of its early inhabitants were purportedly enslaved people looking for somewhere to settle following the ending of the five year apprenticeship period in 1839. It was designated a rural coloured group area under apartheid. A small group of locals have a clear sense of pride in their history, and embrace their connections with slavery which is taken as Pniel’s formative experience. The Freedom Monument – which celebrates emancipation – was reflective of this, and subsequent developments including two further monuments and the museum have advanced this engagement with the past. The museum itself offers a thorough overview of local history, partially laid out in the form of a historical farmhouse, and partially based on interpretive content. There is no exhibition dedicated to slavery at Pniel Museum, however the links between Pniel and slavery are evident at various points. Additionally, staff (local volunteers) are happy to talk about the links both they and Pniel hold with slavery. Perhaps the most important display in terms of slavery is a family tree of the Willemse family. At the top sits a photograph of Adriaan Willemse who is described as ‘a freed slave who settled on the Pniel mission station and became the father of almost 70% of Pniel inhabitants’. The museum functions as something of a community archive featuring donated objects ranging from cutlery to trade implements. There are, however, no objects which belonged to the village’s early and formerly enslaved inhabitants.

Slave Lodge

The Slave Lodge building was first constructed in 1679 by the VOC as housing for the people they enslaved. It was modified over time, and post-British settlement of the Cape was transformed into government offices. After passing through various stages of administrative use – most notably as the Supreme Court – it opened as the South African Cultural History Museum in 1967.

Typical of apartheid-era museology, its displays made no reference to the building’s connections with slavery. Post-apartheid, the museum was brought under the management of southern state umbrella Iziko Museums, and was renamed Slave Lodge in 1998. Although a number of its displays still date from the Cultural History Museum period, new exhibitions have been installed, and the museum now purports to serve as a centre where human rights abuses are discussed and exposed. There is a particular focus on slavery, and racial segregation under apartheid, both through permanent and temporary displays.

The main slavery exhibition is titled ‘Remembering Slavery’ and opened in 2006. This occupies the western wing of the ground floor of the museum. The exhibition offers a comprehensive overview of Cape slavery, with galleries focussing on contextual history, the Slave Lodge building, the middle passage, slave trading routes in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, and a recreation of life in the eighteenth century Slave Lodge. Owing to the paucity of material remnants of slavery at the Cape, the exhibition relies on text to a large extent. Tapping in to the ‘reconciliation’ narrative of the early Mandela years, its overall effect is to portray slavery as a South African history which the country has learned from.

The opposite wing of the building hosts a changing selection of temporary exhibitions which have focussed on human rights abuses including the anti-apartheid struggle and women’s rights. The museum offers a comprehensive education programme with a particular focus on slavery.

Memorial ACTe

On the former site of a sugar factory, Guadelopue's Memorial ACTe stands as a cultural institution that aims to preserve the memory of those who suffered during slavery, as well as to act as a space for discussion on the continuing repercussions. Part of UNESCO's Slave Route project, its main focus is on the challenges of bondage in the Guadeloupe islands. Memorial ACTe was opened in 2015 by then French President, Francois Hollande, and nineteen other heads of state.

The Memorial ACTe is a unique museum, both internally and externally, through its architectural design. It is also a centre for live arts and debates. It aims to provide interpretation through a variety of viewpoints and disciplines, using not only history but ethnology, social anthropology and history of art as well. The history of slavery and the slave trade are explored through a range of archival material, images and artefacts, with visual and audio installations too.

The permanent exhibition space examines the history of slavery from antiquity to the present day, using objects, reconstructions, visual and audio installations and digital interactives. The temporary exhibition space focusses on contemporary forms of artistic expression in relation to slavery around the world. In addition, there is a research centre where visitors can look into their genealogy, as well as a library and a conference hall.

M Shed

M Shed opened in 2011 and is housed in a warehouse on Bristol’s dockside, a clear and tangible link to the history it interprets. The free-to-enter museum focuses on social history, exploring the development of Bristol as a city through people, places and daily life. It is a popular site, attaining over half a million visitors per year since 2013.

Through this local viewpoint, the museum explores Bristol’s involvement with the transatlantic slave trade and the abolition movement in its ‘Bristol People’ gallery which aims to ‘explore the activities past and present that make Bristol what it is.’ Voices from all factions of the slavery debate feature in the display, with proslavery, the enslaved, particularly those who fought for emancipation, and abolitionists all interpreted within dedicated cases. Each case contains a mix of objects, archive materials and text panels to tell the story. Quotations from key figures also bring to life the voices of those who were personally involved: for example, John Pinney, a plantation owner and sugar agent; Hannah More, a writer and Abolition campaigner; John Kimber, a slave ship captain accused (and acquitted) of murder; Silas Told, an ordinary sailor on slaving voyages. These Bristolian voices give different perspectives on how those involved in the trade saw it at the time. Quotations printed around the gallery also provide the views of today’s visitors to the trade. The exhibition also has sections about the legacies of the slave trade within Bristol, particularly in relation to the representation of African or Afro-Caribbean communities in popular culture, the presence of racism in the city, and the legacies of prominent slave owners in some of Bristol's public institutions.

The theme of antislavery also features as the starting point for a display on public protest movements. One case focusses on Thomas Clarkson’s visit to Bristol to collect information against the trade, another on the campaign to abstain from slave-produced sugar in the 18th century and the Bristol bus boycott against racist employment practices in the 20th century. This display then goes on to look at other popular campaigns and protest movements including women’s suffrage, riots, strikes and the Occupy movement. This perspective, situating the abolition campaign as the beginning of a British tradition of society campaigning, is a unique one across UK museums.

In the Bristol Life gallery, the stories of two Black Bristolians look at the new life for the runaway enslaved man, Henry Parker, and the Windrush generation Princess Campbell.

Wedgwood Museum

The Wedgwood company's founder, Josiah Wedgwood I, had the initial idea for preserving and curating a historical collection in 1774. A public museum dedicated to this purpose first opened in 1906, and moved to its present site in 2008. In 2009 the museum won the Art Fund Prize for Museums and Galleries. It underwent further redevelopment in 2015/16. The museum's rich collection of ceramics and archive material tell the story of Josiah Wedgwood, his family, and the business he founded over two centuries ago.

The collections at the museum make up one of the most significant single factory accumulations in the world. They contain a range of things from ceramics, archive material and factory equipment, to social history items that help interpret life in Georgian Britain. Key themes explored throughout the galleries include Wedgwood's links to royalty, the influence of nature on his work and his position as a successful entrepreneur.

On display in the museum also are a small collection of objects which relate to Wedgwood's prominent role in the campaign to abolish the British Slave Trade. Here, the display focusses on the production of the well-known antislavery medallion, which bears the 'Am I Not a Man and a Brother?' image. It also highlights Wedgwood's connection to Olaudah Equiano and the influence of proslavery factions in British society during the eighteenth and nineteenth century.

American Museum & Gardens

The American Museum in Britain is housed in a manor house, built in 1820 by English architect Sir Jeffry Wyatville. It is the only museum of Americana outside the USA and was founded to 'bring American history and cultures to the people of Britain and Europe'. It uses a rich collection of folk and decorative arts to interpret these traditions from America's early settlers to the twentieth century. Living history events bring these stories to life, in addition to changing temporary exhibitions which keep the narrative up to date. The museum opened to the public in 1961 as the brainchild of two antiques dealers.

The museum's collections are a rich source of furniture, portraiture and textiles from America, displayed thematically within period rooms acting as gallery spaces. The 'American Heritage' exhibition, charting the history of America through the narration of key events and people dominates a large proportion of this space. Key collections highlights in this exhibition include Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream' speech and a range of treasures from New Mexico.

Also contained within the 'American Heritage' exhibition is a small display about slavery and abolition in America. The main focal point of this display is a quilt made by enslaved people on a plantation in Texas. Other themes addressed here include the Underground Railroad, prominent abolitionists and the importance of the Civil War in the eventual abolition of slavery.

National Museum of the Royal Navy

The National Museum of the Royal Navy is located in Portsmouth’s Historic Dockyard. Its aim is, ‘to make accessible to all the story of the Royal Navy and its people from earliest times to the present.’ The museum, housed in a former naval storehouse, receives almost one million visitors per year.

Through five galleries, the museum charts the development of the Royal Navy and the experiences of the people who served in it. In the ‘Sailing Navy’ gallery, visitors can find out about the initial professionalisation of the navy during the eighteenth century. There are exhibits which discuss rations, health, hand-to-hand combat and available honours.

In this gallery, there is also a section of the display which discusses the other roles played by the Royal Navy, in addition to participation in conflict. The most striking exhibit in this section is a diorama model which depicts the use of the Royal Navy in the suppression of the slave trade, after the abolition of 1807. A little-known story in the British antislavery narrative, the model is accompanied by interpretive text which provides some context about the transatlantic slave trade and the campaign to abolish it. In addition, it also goes some way to outlining the prolonged involvement of Britain in eliminating other European slave trading in the years following 1807. While there are no artefacts used in narrating this story, the diorama itself provides a visualisation of the practice of suppression.

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery has over forty display galleries that explore the development of Birmingham as a city, through its diverse communities. Since opening in 1885, the museum has built a vast collection of social history, art, archaeology and ethnographic items. It is one of nine sites managed by Birmingham Museums, the largest museums trust in the UK, whose vision for their service is, ‘to reflect Birmingham to the world, and the world to Birmingham.’ Housed within Birmingham's council buildings in the city's Chamberlain Square, the site welcomes around one million visitors a year.

Slavery and abolition feature as themed displays within the ‘Birmingham: Its People and Its History’ gallery, which dominates the third floor of the Victorian museum. Initially developed as part of the 2007 bicentennial commemoration activities, the displays highlight the contradictory nature of Birmingham’s relationship with the slave trade. Visitors are informed, through both interpretive text panels and collections artifacts on display, about the goods manufactured in Birmingham that were taken to Africa to trade in exchange for human beings. Simultaneously, the presence of antislavery activists in the city is explained, with digital interactives, portraits and abolitionist material culture all illustrating the role of Quakers and other prominent abolitionist figures, including Joseph Sturge and Olaudah Equiano.

The displays also alert visitors as to the existence of modern slavery by a panel headed with the words, ‘Around the world, people are still enslaved today.’ The visitors are then invited to leave their own comments as to how society can help to stop it in their community and around the world.

The Rum Story: The Dark Spirit of Whitehaven

‘Rum Story: The Dark Spirit of Whitehaven’ is a museum housed inside the former warehouse, office and shop of the Jefferson’s Rum Company in Cumbria. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth century Jefferson's would have been in receipt of slave-grown produce from the Caribbean, which would have been stored and processed in the museum's building.The museum opened in 2000 as part of the town’s regeneration project and aims ‘to bring history to life.’

On entering the museum, visitors walk through a series of room settings, from the African jungle at the beginning of enslavement, to a reconstruction of a slave ship hold complete with mannequins, and finally plantation offices . These room settings offer a very immersive experience, complete with opportunities for total sensory engagement; scent boxes, samples for tasting on exit and soundtracks all the way through.

The collections consist mainly of archival material which illustrates the company's connection to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, and how that made Whitehaven a prosperous port town. Interpretive panels explain the room settings, and diorama scenes with mannequins illustrate to visitors the way things were during the period, for both the enslaved and the workers in Jefferson's factory. The greatest asset that the museum has is the building itself, which provides a true, tangible link to the trade and its legacy on the local community.

Cowper & Newton Museum

The Cowper & Newton Museum is a very small, local museum managed by a charitable trust and staffed predominantly by volunteers. The museum is situated in Orchard House, the home of poet and author William Cowper between 1768 to 1786. Since it opened in 1900, the museum has focussed on telling the story of Cowper’s life in the thriving Georgian market town of Olney, Buckinghamshire. The museum also examines Cowper's relationship with his friend and neighbour, slave-trader turned ordained priest and abolitionist, Reverend John Newton.

The museum’s mission is for visitors to ‘relive Georgian life in Olney.’ Using items of personal collections relating to both of the museum’s namesakes, the displays bring the house to life in the form of period room settings combined with display cases and interpretive panels. Both Cowper and Newton published writings against the slave trade and corresponded with other abolitionists, including William Wilberforce. The displays provide some context on the slave trade before outlining Cowper and Newton’s involvement in abolition. This is represented through a range of objects including archive material, portraits and furniture both from the museum’s collection, and loaned pieces from Wilberforce House Museum, Hull.

As well as being a theme which runs throughout the whole museum, with Cowper’s ‘The Negro’s Complaint’ on display in the Georgian History Room for instance, there is one particular room on the first floor of the house which focuses predominantly on the slave trade and abolition. Like most of the museums analysed here, the interpretive panels in this display were created using funds made available for the bicentenary in 2007.

Wisbech and Fenland Museum

The Wisbech and Fenland Museum is one of the oldest, purpose-built museums in Britain. With its origins dating back to 1835, visitors are welcomed into a real ‘treasure house,' with collections housed in original nineteenth century cases. The museum is free to enter and focusses on local history, housing the vast and varied collection of the town’s literary and museum societies. Using these, the museum presents displays on a range of themes relating to key local industries, wildlife, archaeological finds and important people from the area.

One of these important people is Wisbech-born Thomas Clarkson, and it is through him that the theme of antislavery fills several of the largest cases in the main gallery. Using a combination of personal collections, archive material and objects linked to the wider slave trade (notably whips and a manacle), the museum follows Thomas Clarkson’s contribution to the abolition campaign, both in Britain and abroad. The museum also exhibits the narrative of Thomas’ brother John Clarkson who was instrumental in facilitating the movement of freed-slaves from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Sierra Leone.

This display was developed as a larger, standalone exhibition for the 2007 bicentenary entitled ‘A Giant with One Idea,’ but this was reduced following the end of the commemorations as funding was withdrawn.

People's History Museum

The People's History Museum (PHM) is Britain’s national museum of democracy, telling the story of its development in Britain; past, present and future. It is located in Manchester, the world's first industrialised city and aims to ‘engage, inspire and inform diverse audiences by showing there have always been ideas worth fighting for’. Attracting over 100,000 visitors a year, with free entry, the museum outlines the political consciousness of the British population beginning with the Peterloo Massacre in 1819. The British transatlantic slave trade and the abolition movement feature in this discussion early on in Main Gallery One. In a small display, the interpretation discusses the role of slave-produced cotton in the rise of Manchester as an industrial powerhouse. It goes on to describe the important role that the people of Manchester had in supporting the abolition campaign. The focus is on the local experience. This is also illustrated with one of the exhibition’s key interpretive characters, William Cuffay, a mixed-race Chartist leader whose father was a former slave. In Main Gallery Two, the displays are brought closer to the present day, other issues explored include anti-racism and attitudes towards migration and multiculturalism. There is a clear link, although not explicitly expressed, in the interpretive text between these ideas and the lasting legacies of Britain's involvement in the slave trade.

Wilberforce House Museum

Wilberforce House Museum is one of the world's oldest slavery museums. It opened in 1906 after the building, the house where leading abolitionist William Wilberforce was born, was bought by the Hull Corporation to preserve it for reasons of learning and of civic pride. Initially a local history museum, at the centre of Hull's historic High Street, the collections soon expanded through public donations and, unsurprisingly, these donations focussed heavily on items relating to Wilberforce. Today the museum and its collections are owned by Hull City Council and managed by Hull Culture and Leisure Limited. It forms part of Hull's 'Museums Quarter' alongside museums on transport, local social history and archaeology. In addition to the Wilberforce displays, the museum also features period room settings, silver, furniture and clocks, as well as a gallery exploring the history of the East Yorkshire Regiment.

The galleries at Wilberforce House Museum tell many different stories. An exploration of the history of the house welcomes visitors into the museum, followed by displays about William Wilberforce from his childhood, to his work and his family life. These galleries have examples of costume, books, domestic items and even the 1933 Madame Tussauds wax model of Wilberforce himself. Up the grand cantilever staircase, installed by the Wilberforce family in the 1760s, the displays continue. Here they look at the history of slavery and the origins of the British transatlantic slave trade. One gallery contains items that illustrate the richness of African culture prior to European involvement, dispelling the traditional myth that Africa was empty and uncivilised before the intervention of the Western world. Following that, the exhibition narrative goes on to look at the process of enslavement, the logistics of the trading system, the Middle Passage and slave auctions. Again, a wide range of collections are used to illustrate the informative panels. This is repeated in the displays about plantation life and resistance.

Of course no museum about William Wilberforce would be complete without an exhibition on antislavery and the abolition movement. This is extended with two galleries which look at the legacies of such a campaign in terms of modern slavery and human rights today. There are opportunities in these galleries for visitors to provide their comments and opinions, through several interactives, as well as engage with ideas as to how they can actively participate in today's campaign to end modern slavery.

National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum is the largest maritime museum in the world. It forms part of the Royal Museums Greenwich UNESCO World Heritage Site. The NMM houses ten galleries that all showcase Britain’s Maritime History. Its mission is 'to enrich people’s understanding of the sea, the exploration of space, and Britain's role in world history’. ‘The Atlantic Worlds Gallery,' launched in 2007 for the commemoration of the bicentenary, charts the interconnections between Britain, Africa and the Americas between 1600 and 1850. The gallery is about the movement of people, goods and ideas across and around the Atlantic Ocean from the 17th century to the 19th century. The connections created by these movements affected people across three continents, impacting on their cultures and communities and shaping the world we live in today. Four main themes are explored within the gallery, including exploration, war, enslavement and resistance. These displays benefited extensively from the museum's purchase of the Michael Graham-Stewart Slavery Collection in 2002. 'Atlantic Worlds' charts the triangular trade through African civilisations, enslavement and the Middle Passage, and the abolition movement. It recounts the stories of some of the people involved in the resistance movement and the campaign for the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade – including Toussaint l’Ouverture, Olaudah Equiano and Samuel Sharp whose acts of resistance and rebellion were crucial to the turning of European public opinion against the trade. Its narrative also goes beyond the achievement of legal abolition in Britain, to include discussions of the Royal Navy's involvement in suppressing the trade world wide.

Museum of London Docklands

The Museum of London Docklands houses the Port and River collections of the Museum of London. The aim of these museums is to showcase the growth and development of London, from the Roman era through to the present day. In a period of expansion for the Museum of London, the Museum of London Docklands was opened in 2003 in a Grade I listed warehouse on West India Quay, the historic trading heart of London.

Due to its location in a warehouse which would very likely have stored sugar, and other slave-produced items, the history of the transatlantic slave trade and its impact on London fits well within this space. ‘London, Sugar and Slavery’ was originally produced in 2007 as part of the bicentenary commemorations but has since become a permanent part of the museum. The displays have a local focus, supported through a wide range of objects, and consider the impact of the slave trade on London historically and today.

On entering the gallery visitors are met with a list of ships that traded slaves from the West India Quay- placing them right there in the story. Next there are discussions of the economics of slavery, and indications of how the money made from it changed the city of London forever. The exhibition also includes discussions of resistance, and abolition- centring the movement on the mass movement in the wider population with a case entitled ‘Abolition on the Streets.’ To bring the display up to date there is a discussion of representations of black people in popular culture, with objects including children’s books, film memorabilia, toys and prints, in line with a further piece on racism in London.

International Slavery Museum

The International Slavery Museum (ISM) is the first museum in the world to focus specifically on slavery, both historical and modern. Managed by National Musuems Liverpool, it opened to great acclaim in 2007 and has since welcomed over 3.5million visitors. Through its displays and wide-ranging events programme, the ISM aims to tackle ignorance and misunderstanding in today’s society by exploring the lasting impact of the transatlantic slave trade around the world. On entering the ISM, visitors immediately arrive in a space designed to provoke thoughts and discussion- the walls are etched with powerful quotations from historical figures and contemporary activists, many from the African diaspora. There is a display of West African culture, designed to showcase the breadth and depth of African civilisation before the devastation caused by the transatlantic slave trade, which includes examples of textiles, musical instruments and other ethnographic material. The display then goes on to look at the trade itself; the logistics, the processes and who benefitted on one hand, whilst also exploring the experience of the enslaved through multisensory interpretive techniques, including an emotive film of what the Middle Passage may have been like. All of these displays are supported by the rich, local archival collections, drawing on Liverpool’s own history as a prosperous, slave-trading port. Moving forward along a chronological timeline, the exhibition then covers abolition, significantly beginning with the acts of resistance from the enslaved themselves, through to organised abolition movements and then discussing the continued fight for freedom through the post-emancipation then civil rights era, right into the twenty-first century. The lasting legacies of the trade are thoroughly examined, from racism and the under-development of African countries, to the spread of African culture and diverse nature of Liverpool’s communities. A unique feature of the ISM is its ‘Campaign Zone’, opened in 2010, which houses temporary exhibitions just off the main gallery space. These are frequently run in conjunction with campaign organisations and usually focus on aspects of modern slavery, highlighting to visitors that it is very much still a live issue and not one that has been relegated to history. Recent exhibitions in this space have included 'Broken Lives' organised with the Daalit Freedom Network and 'Afro Supa Hero' with artist Jon Daniels.