Wall of Dignity

In 1967, Detroit experienced one of the most brutal race rebellions in its history. In the early hours of June 23rd, the police raided an after hours club. Expecting to find a few people inside, they instead found 82 individuals. Everyone was arrested and escorted from the building, and as this happened, a crowd of 200 people gathered. As the night slowly crept into the next morning, violence and looting emerged on Twelfth Street, and the Detroit rebellion was underway. The rebellion carried on for five days. Mayor Jerome Cavanagh initially sought to quash the uprising with police units, but failed to gain support for this tactic as many African Americans in the city deemed the police the problem. In 1968, a year after Detroit’s violent rebellion, a local community organizer named Frank Ditto contacted muralists Bill Walker and Eugene Eda Wade, asking them to create a mural in his local community. Wanting to create a mural that could project an expression of black unity during a time of racial pain, Walker and Wade set about creating the Wall of Dignity. Painted on the façade of an abandoned ice-skating rink, the mural was broken down into three main sections. The top half of the mural depicted diasporic scenes of ancient life in Africa, whilst the middle section functioned as a collection of portraits of prominent African American men and women who sacrificed their lives by fighting for black liberation throughout history. The faces of Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Mary McLeod Bethune and Stokely Carmichael line the wall. The bottom section of the mural, enveloping the words ‘The Wall of Dignity’, depicts scenes of enslavement. Silhouetted figures of manacled men and women stretching their chains taut as they stretch for freedom are countered by figures raising their unshackled hands to the sky in moment of liberty. Towards the left-hand side of the mural, a poem titled ‘Slave Ship’ reads:

I am a prince, speak with respect I shall not be chained to your Bloody deck To live in this filth and stench? Ooooaaee a poor soul have died on his bench This meaning does burst the drums of my ears Long hours from my home seem like years A prince to ear the food of jackals!! My arms, my leg bleed from your shackles You must look to my woman What had been done to one so sweet, so mild? AAAHHH! Within here was my child. Strange tongued-golden haired man I will not journey to your land. Leave me…leave me be… Cast my carcass into the sea The sea.. Black..Black like me.

The Crenshaw Wall

In 2000, a graffiti collective called Rocking The Nation (RTN) began The Crenshaw Wall, colloquially known as The Great Wall of Crenshaw. At 7,787 feet long, the mural has become a landmark for the area. The timeline depicts African American history, and features the antislavery figures Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, as well as Marcus Garvey, black soldiers from World War I, II and Vietnam, and Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie. A shackled slave breaks free from his chains and evolves into an athlete, American footballer and basketball player. Further along the mural are Black Panther Party leaders alongside Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X. The mural starts with a black woman breathing life into the mural and ends with a couple giving birth.“We finally get the chance to paint the Crenshaw Wall, and bring some black awareness to the Crenshaw Wall – to teach the history of our people, to teach our people to be proud, to teach our people love, and where we came from and where we might possibly end up,” explained Enk One of RTN.Over a decade later, the mural requires restoration and protection. RTN are working towards this goal, as well as designating the mural a historical landmark, renaming the block ‘Crenshaw Mural Square’ and developing an app that gives a visual tour of the mural.

Labor History Mural

This mural in New Bedford titled Labor History Mural and painted by Irish muralist, Dan Devenny, is a short distance away from where Frederick Douglass first lived in freedom. It is on a wall near the Bristol County Probate Court.On September 18, 1838, Douglass settled here in New Bedford after escaping from slavery in Maryland, with the help of his soon-to-be wife, Anna Murray. It was in New Bedford where Douglass experienced, for the first time, what it was like to live as a free man. His abolitionist identity started to take shape. He read his first copy of The Liberator, became a licensed preacher, gave a speech in 1839 that denounced the proposal that free slaves be forced to emigrate back to Africa, and was hired as an agent by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society (MASS). In 1841, after attending a regional convention for the followers of William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass felt compelled to speak about his time in bondage. Inspiring the Garrisonian audience, he was shortly recruited as a lecturer for MASS. “Many students in New Bedford never learn of the importance of Frederick Douglass and his relation to the civil rights movement and this city,” said Massachusetts Senator Mark Montigny. “This mural will be a constant reminder of his prominent leadership and what he means to New Bedford.”

Ancestral Roots

Pontella Mason is one of Baltimore’s unsung visual artists. He has created murals for the Anacostia Community Museum, former President Jimmy Carter, and several other public organisations. His murals depict African American life and the diaspora. In 1999, he created the extensive mural Ancestral Roots, which depicts the antislavery heroes Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Frederick Douglass, as well as Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Notorious B.I.G., Tupac, Shirley Chisholm, and Marcus Garvey.

![Curtis Lewis, African Amalgamation of Ubiquity, 9980 Gratiot Avenue, Detroit, Michigan, 1985 [destroyed in 2013].jpg Curtis Lewis, African Amalgamation of Ubiquity, 9980 Gratiot Avenue, Detroit, Michigan, 1985 [destroyed in 2013].jpg](https://486312.frmmmguz.asia/files/square_thumbnails/3ac63b31ad894031e7c74b99651ace4a.jpg)

African Amalgamation of Ubiquity

In 1985, muralist Curtis Lewis created a mural on the side of a drug rehabilitation centre on Gratiot Avenue, Detroit, Michigan. The building belonged to Operation Get Down and included the antislavery figures Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, as well as Malcolm X, Mary McLeod Bethune, Jesse Jackson, Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King Jr., W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Ida B. Wells, Marcus Garvey and Nelson Mandela, alongisde Egyptian, Nubian and pharaoh figures. The man who breaks free of his chains in the centre of the mural holds a sign that reads, “Behold my people, arise, stand strong and proud, for ye come from pharaohs, emperors, kings and queens.” The mural was destroyed in 2013.

![John Weber, All Power to the People, Cabrini-Green Public Housing Development, 357 W. Locust St, Chicago, 1969 [destroyed].jpg John Weber, All Power to the People, Cabrini-Green Public Housing Development, 357 W. Locust St, Chicago, 1969 [destroyed].jpg](https://486312.frmmmguz.asia/files/square_thumbnails/5bee9c55de2e128c0239ac4a0793b9c0.jpg)

All Power to the People

In 1969, in the courtyard of Saint Dominic’s Church in Cabrini-Green, John Pitman Weber painted All Power to the People with a team of black teenagers. The 37-foot-long mural put the antislavery leader Frederick Douglass alongside Malcolm X, Huey P. Newton and Erika Huggins on the right-hand-side. On the left are skeletons of police officers and a statement by the leader of the Chicago Black Panther Party, Fred Hampton: "Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win." A raised Black Power fist, enveloped by flames, holds broken chains in a symbol of self-emancipation. A few months after the creation of this mural, Fred Hampton was shot and killed by the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO. Weber was a white Harvard graduate and Fulbright scholar. The mural was one of the first collaborations between untrained community residents and a trained artist, a method that became common practise for American community murals.

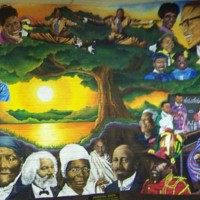

Black Seeds

In 1991, a group of artists – Eddie Orr, David Mosley, William T. Stubbs, Norman Maxwell and Michael McKenzie – collaborated to paint “Black Seeds” on an empty wall in Leslie N. Shaw Park on Jefferson and 3rd Avenue in Los Angeles. The idea for the mural, which appears as an African American tree of life, came from Vietnam veteran and local activist Gus Harris Jr. He recalled how little he learned about African American history in school. He wanted to create a public mural about black individuals who made an important contribution to society.The mural was created under the Social and Public Art Resource Center's 1990-91 “Neigborhood Pride: Great Walls Unlimited” mural program and features the antislavery leaders Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, as well as Booker T. Washington, Thurgood Marshall, Mary McLeod Bethune, Malcolm X, George Washington Carver, Paul Robeson, Stevie Wonder, Shirley Chisholm, Martin Luther King Jr., and Jesse Jackson. The mural was restored by Moses X. Ball to include Barack Obama after 2008. The original canvas upon which the mural was based hangs in Oaks Jr. Market Corner Store at 5th and Jefferson.

Lincoln Legacy

This large mural by Joshua Sarantitis, Lincoln Legacy, can be read from left to right, moving from Africa to America. The shape of Africa adorns the backdrop until the wooden boards of the slave ship transform into the American flag. Around the young child’s neck are three medallions: Abraham Lincoln’s face, Josiah Wedgwood’s abolitionist icon “Am I Not a Man and a Brother,” and Frederick Douglass' face. Made up of over 1 million glass mosaic tiles, it is the largest Venetian glass tile mural in Philadelphia at over 10,000 square feet. Located a block away from the Liberty Bell and Independence Mall, it is one of the few murals to be created in Philadelphia’s wealthier districts.

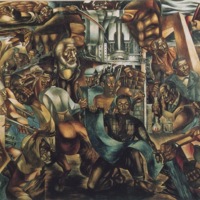

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass

In 1972, artist LeRoy Foster created this mural for the Douglass Branch of the Detroit Public Library. The mural depicts a meeting between Frederick Douglass and John Brown that took place on March 12, 1859, seven months before Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. The mural contains three likenesses of Douglass in various stages of his life – the most prominent being the shirtless figure in the centre of the mural. The second largest figure of Douglass portrays him with the leonine, statesmen persona that he embodied later in his life. Finally, the smallest Douglass likeness is the seated figure speaking with John Brown. This small scene marks a pivotal moment in Douglass' life. In 1859 he had to make the decision between fighting with Brown (embodying the chain-breaking version of himself in the mural), or surviving to become a political leader. Choosing not to take up arms at Harper's Ferry, an attack that led to the execution of Brown for treason, Douglass chose the elder statesman person - and lived to 1895.

The Founding of Chicago

In 1933, Aaron Douglas created a mural titled The Founding of Chicago. The mural depicts the role of slaves and free African Americans in the creation of American cities across the country. Standing in the centre of the mural, the Haitian founder of Chicago, Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable, surveys the urban environment he helped to construct. Behind du Sable, a shackled woman raises her child to view the towering metropolis. Today the mural is housed at the Spencer Museum of Art, at the University of Kansas.

Into Bondage

In spring 1936, as part of the “healing process of the nation” during the aftermath of the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas. Although African Americans took part in the exhibition, their designated section of the fair was in the Hall of Negro Life; a separate building isolated from the main path by a row of cedar trees and shrubs. One of the murals on show was Aaron Douglas’s Into Bondage. Douglas’ murals gave African Americans a new identity at the Exposition by drawing on a usable antislavery past to develop an alternative narrative of black history: no longer passive enslaved supplicants, African Americans are empowered liberators. Douglas layered the mural with a guide for potential resistance.

Aspects of Negro Life

Two years prior to the Texas Centennial Exposition, Aaron Douglas created a four-part mural series titled Aspects of Negro Life, to be housed in the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, the Schomburg Center. The various panels portray black history from slavery through to present. The various panels are titled, The Negro in an African Setting, From Slavery Through Reconstruction, Song of the Towers, and An Idyll of the Deep South, and depict the breaking of chains, the idea of self-emancipation, liberation, and the celebration of African culture.

I Am, Yo Soy/Wall Therapy

As part of a Rochester WALL\THERAPY mural project in 2013, muralist Lunar New Year used Trayvon Martin, a young Frederick Douglass, and a local resident called Christopher to depict three possible paths of African American manhood in his mural I Am/Yo Soy. The young boy on the edge of the mural pleads to the North Star in the sky in a position that echoes Josiah Wedgwood’s famous 18th-century "Am I Not a Man and a Brother" medallion. An older version of Douglass then sits on the right side on the mural, as the only figure beyond the real and painted chain link fences.Lunar New Year, who is an Ecuadorian American Newark-based artist, explained that the mural is about “the history of institutionalized injustice in the USA… Injustice forged Frederick Douglass’s character, robbed Trayvon Martin of his life and [it] is up to us, to dictate what future awaits for young 7 year old Christopher from Rochester.”

Wall of Black Heroes

In 2006, muralist Joseph Tiberino, along with his sons Gabe and Raphael, painted Wall of Black Heroes for the African American Museum of Philadelphia. When creating the mural, the idea was to provide a portable piece of work that would later be housed in the streets. Measuring 4ft by 12ft, the mural was created on such a scale so as to provide the audience with the sense that the figures of history were life-size. The mural takes the audience on a historical journey, starting with a self-emancipating shackled slave, then moving to the abolitionists Frederick Douglass andHarriet Tubman, then Angela Davis and Malcolm X, Spike Lee, Paul Robeson, Louis Armstrong and Martin Luther King Jr. The mural is now on the side of the Municipal Services Building next to City Hall.

![John Weber, Wall of Choices, Christopher Settlement House, N Greenview Ave and W Altgeld St, Chicago 1970 [destroyed], detail.jpg John Weber, Wall of Choices, Christopher Settlement House, N Greenview Ave and W Altgeld St, Chicago 1970 [destroyed], detail.jpg](https://486312.frmmmguz.asia/files/square_thumbnails/9fc1c6430ac66c245ed40da9a8d9ad6c.jpg)

Wall of Choices

In 1970, John Pitman Weber of the Chicago Public Art Group created a mural on the wall of the Christopher Settlement House on the north side of Chicago. The mural faces a children’s playground in a predominantly white working-class area of the city and according to Weber, the neighbourhood’s anxiety regarding racial tensions in the community only emerged during the creation of the mural and related discussions with local residents. Working together, Weber and the local residents agreed that the racial concerns needed to be surfaced, and the mural would serve this purpose. It depicts narrative scenes across the wall, including daggers and guns held by both black and white individuals, black hands in handcuffs under the phrase “free all political prisoners,” (something that the Black Panther Party was pushing for in the 1960s and 1970s), and a black hand shaking a white hand under the faces of Frederick Douglass and the radical white abolitionist John Brown, who are both identified on the mural as Freedom Fighters. The mural had been destroyed by the late 20th century.

![Walter Edmonds & Richard Watson, Painting 7, Church of the Advocate [African American Episcopal Church], 1801 W. Diamond St, Philadelphia, 1974.jpg Walter Edmonds & Richard Watson, Painting 7, Church of the Advocate [African American Episcopal Church], 1801 W. Diamond St, Philadelphia, 1974.jpg](https://486312.frmmmguz.asia/files/square_thumbnails/e327c85c758c9839bb0746ded74d8668.jpg)

African American Experience

During the Civil Rights Movement, African American activists held rallies and conventions at the Church of the Advocate. But people started to notice the absence of black figures from the church artwork. Father Washington remembered: “there were people who came into the church, and as they looked around they saw nothing and no one, including the figures in the stained glass windows, with whom they could identify. Everything they looked at was white, white, white. ‘How can we look at this white image for our liberation when it is our experience that it is the white man who is our oppressor?’" Upon hearing these questions, Father Washington realised that “we could see the black experience revealed and defined in religious terms, and find parallel situations in what we read in the Old Testament every Sunday.” He commissioned a series of murals for the side of the church, painted by Walter Edmonds and Richard Watson, that show parallels between the experiences endured by Hebrew slaves in Egypt and those suffered by African slaves in America.

The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America

In 1941, the artist Charles White was awarded $2000 from the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship for an ambitious project that included the creation of Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America. Two years later, he unveiled the mural at the Hampton Institute in Virginia.The central figure has chains around his wrists that also loop around the necks of three other figures. But the shackles on the figure’s wrists are ready to be broken by the abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Nathaniel Turner, Denmark Vesey, Harriet Tubman and Peter Still.

![Eugene 'Edaw' Wade, Cramton Auditorium Mural, Howard University, 1976 [destroyed].jpg Eugene 'Edaw' Wade, Cramton Auditorium Mural, Howard University, 1976 [destroyed].jpg](https://486312.frmmmguz.asia/files/square_thumbnails/9b88d25ab0cf2bbdaa447fb07c56eee8.jpg)

Cramton Auditorium Mural

In 1976, Eugene Eda Wade created a mural at Howard University in Washington D.C. The mural depicts the abolitionists Sojourner Truth and Nathaniel Turner attempting to break chains, as well as the abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, and leaders Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. The mural has now been destroyed.

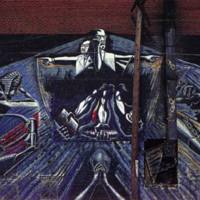

Wall of Meditation

In 1970, Eugene Eda Wade painted the Wall of Meditation on the exterior façade of the Olivet Community Center. Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. anchor the middle of the mural, and are surrounded by Egyptian figures on the left, and enslaved figures breaking free from their chains on the right.