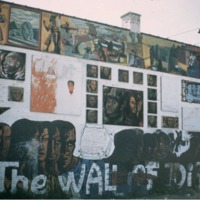

Wall of Dignity

In 1967, Detroit experienced one of the most brutal race rebellions in its history. In the early hours of June 23rd, the police raided an after hours club. Expecting to find a few people inside, they instead found 82 individuals. Everyone was arrested and escorted from the building, and as this happened, a crowd of 200 people gathered. As the night slowly crept into the next morning, violence and looting emerged on Twelfth Street, and the Detroit rebellion was underway. The rebellion carried on for five days. Mayor Jerome Cavanagh initially sought to quash the uprising with police units, but failed to gain support for this tactic as many African Americans in the city deemed the police the problem. In 1968, a year after Detroit’s violent rebellion, a local community organizer named Frank Ditto contacted muralists Bill Walker and Eugene Eda Wade, asking them to create a mural in his local community. Wanting to create a mural that could project an expression of black unity during a time of racial pain, Walker and Wade set about creating the Wall of Dignity. Painted on the façade of an abandoned ice-skating rink, the mural was broken down into three main sections. The top half of the mural depicted diasporic scenes of ancient life in Africa, whilst the middle section functioned as a collection of portraits of prominent African American men and women who sacrificed their lives by fighting for black liberation throughout history. The faces of Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Mary McLeod Bethune and Stokely Carmichael line the wall. The bottom section of the mural, enveloping the words ‘The Wall of Dignity’, depicts scenes of enslavement. Silhouetted figures of manacled men and women stretching their chains taut as they stretch for freedom are countered by figures raising their unshackled hands to the sky in moment of liberty. Towards the left-hand side of the mural, a poem titled ‘Slave Ship’ reads:

I am a prince, speak with respect I shall not be chained to your Bloody deck To live in this filth and stench? Ooooaaee a poor soul have died on his bench This meaning does burst the drums of my ears Long hours from my home seem like years A prince to ear the food of jackals!! My arms, my leg bleed from your shackles You must look to my woman What had been done to one so sweet, so mild? AAAHHH! Within here was my child. Strange tongued-golden haired man I will not journey to your land. Leave me…leave me be… Cast my carcass into the sea The sea.. Black..Black like me.

Wall of Truth

Although sharing an address with the famous Wall of Respect, the Wall of Truth was different. Whilst the Wall of Respect exalted black role models, leaders and liberators, the Wall of Truth wove negative scenes of poverty, brutality and racism into the fabric of the urban environment. Rather than promoting racial pride, it highlighted racial disparities. “The intent on the opposite side [of the road] was that things had gone more militant,” muralist Eugene Wade explained: “more blackness was needed in terms of representing the Black Power symbol and the whole thrust of what was happening in the black community.” Wade notes that “people were getting angry and fed up, so what we were trying to do was implement the attitude and the mood."The Wall of Truth was a significantly larger mural than its Chicago neighbour, the Wall of Respect. It spanned the length of an apartment building, and wrapped around onto an adjoining wall. It contained nine separate narrative panels and was one of the first instances that a radical black past was visualised in the streets through the antislavery leaders Frederick Douglass and Nathaniel Turner, as well as Mary McLeod Bethune, W.E.B. Du Bois, H. Rap Brown, Stokely Carmichael, Marcus Garvey, Huey P. Newton, Fred Hampton, and Malcolm X.

Wall of Respect

The Wall of Respect was the first exterior African American mural in the United States. Painted by OBAC (Organisation of Black American Culture), it underwent three main phases, as shown throughout the photographs here. Its creation was an inclusive process, asking local residents to decide which black heroes should be included in the mural. This was an integral step in the mural-making process because “any muralist who’s doing anything of a thoughtful nature should always have an input from the community,” artist Bill Walker observed. “You can’t do things that make people think they’re not a part of things.” Compiling a newsletter and consulting local militant street gangs, OBAC wrote a list of historic and contemporaneous figures to be memorialised on the wall, before waiting for their approval. “The militant [members of the community] were the ones that defined who would go on the wall and who would not,” artist Eugene Eda Wade remembers in a 2017 oral history interview. The choices were figures from the past and present who “charted their own course” through life and “did not compromise their humanity,” including the antislavery leader Nathaniel Turner, as well as James Brown, James Baldwin, Thelonious Monk, Malcolm X, Nina Simone, Claudia McNeil, Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Elijah Muhammad, Gwendolyn Brooks and Muhammad Ali. By celebrating radical black heroes of the past and present, the mural became a site of black cultural heritage and an unofficial landmark on Chicago’s southside. It also catalysed a national mural movement, with more than 300 murals painted in Chicago alone over the next few decades. In 1971, the mural was destroyed in a fire.

![Leroy White, Wall of Respect, Up You Mighty Race, Leffingwell & Franklin Aves, St. Louis MO, 1968 [destroyed 1980s].jpg Leroy White, Wall of Respect, Up You Mighty Race, Leffingwell & Franklin Aves, St. Louis MO, 1968 [destroyed 1980s].jpg](https://486312.frmmmguz.asia/files/square_thumbnails/ccbe25581b885dd6ea7ad25405af90fe.jpg)

Wall of Respect/Up You Mighty Race

In 1968, after the success of Chicago’s Wall of Respect in 1967, muralist Leroy White painted Wall of Respect/Up You Mighty Race in St. Louis, Missouri. The mural was self-sponsored. After seeing Chicago’s Wall of Respect in Ebony, muralists in St. Louis were inspired to create public art in the Carr Square area of the city. The mural was completed by a coalition of individuals from civil rights groups, including CORE, ACTION, and the Zulu 1200s. It displayed a pantheon of black heroes, including the antislavery leaders Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Marcus Garvey. The mural quickly became a hub of black activism—bringing together artists, performers and political figures in a series of concerts and rallies at the site. But it was vandalised during the 1970s, and its building was razed in the 1980s.