Collection

Theme

Country

Date

Location

Type

8 results

Photography and the Congolese Diaspora

This collection documents an art commission funded by the Arts Council England. Photographer Letitia Kamayi was invited to respond to an archive of photography produced by the British missionary Alice Seeley Harris during her time in the Congo Free State in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Alice took over 1000 photographs depicting Congolese life, however, it is her images of the atrocities perpetrated in pursuit of rubber that have become internationally famous. This project enters into a photographic dialogue with those images to think about the nature of the archive and the politics of representation.

Born in the Democratic Republic of Congo but raised and residing in London, Kamayi’s interests lie in the introduction of self-representation for Black Bodies, the Congo, and Africa more broadly. Using the medium of photography and art, her work draws on personal experiences, lost memories, and the question of identity. Whilst primarily working with medium format, she also experiments with found images and family archives.

Working with the Congolese community in London, Kamayi has created an alternative archive of life and labour within the diaspora. Disrupting the power of the colonial archive to fix the subjectivity of the sitter, Kamayi’s work challenges ideas about Congolese identity which have their roots in the representations of the colonial period. Her images engage with a process of self-empowerment through self-representation. In documenting the lives of both everyday people, as well as those who continue to campaign for rights and equality in the Democratic Republic of Congo, her archive rep- resents the richness of contemporary Congolese life.

Artist’s Statement

Kongo: You Should Know Me was my selfish way of learning more about my past, my ancestors through the images of my kinfolk.

We have the real stories that narrate the true history of Congolese people and life which all of you were too blind to see.

Here is the Congo you should know!

There is a host of missing stories not recorded, stories that my family and friends families experi- enced. Chapters and verses missing from the identity of the Congolese narrative.

Thus Kongo: You Should Know Me evolved to Kongo Archives.

Kongo Archives is extremely personal to me not merely because I am Congolese but also because there is a lot about my country I do not know and am searching for.

I believe it is also something desperately needed, especially as our country’s political structure hangs in the global balance.

It’s a necessity even!

Culture; traditions; customs; language and pretty much every thing has always been passed down orally through the stories in African customs, and now too many of those who did the passing down are fast passing away, taking with them all our history and rightful heritage.

Taking away my rightful heritage, my story, my future and connection to a national identity.

It is a cliche to say, however Kongo Archives gives a voice to every Congolese person, travelling further than just those within the confines of the project.

The archives is the stories of the past, the present and a storage unit where futures can be placed when they become part of our inevitable past.

It [Kongo Archives] is here to topple the power structures of the single story of Congolese identity, working to reform the world’s understanding of, and have embedded notions questioned of a people whose stories and lives were second to the arrival of colonial history and identity killers.

Bringing light to the stories which humanise the “so-called beasts from the dark continent” which continues till this day to suffer from decades of war and conflict whilst also being the wealthiest in natural minerals; culture and fight for peace one day.

Being Congolese I see our hidden presence in the “strangest” places, though this should not be a “strange” sight, this is the importance which representation brings! Change to people’s (and my own) opinions and views of those they are not well informed about.

Kongo Archives will bring light to the multilayers of the Congolese people both residing in and out of The MotherLand.

It is important to have this representation to solidify the very absent Congolese presence outside of the Democratic Republic of Congo, in places such as London; Paris and Belgium as a positive dis- play of unity; positive contribution and patriotism.

Kongo Archives aims to bring the Congolese heritage full circle through exposing the parts of our (Congolese) past and current state the world has and continues to fail to reveal. Breaking down the stereotypes of the poorest; “most dangerous place on earth to be a woman” to a country with a vast potential of peace; unconditional source of love and fight given the chance for change within it’s power structures.

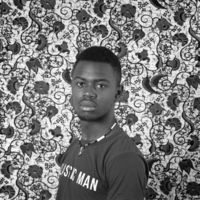

O.M. Kitenge

O.M. Kitenge, D.R. Congo.

2nd Generation Congolese, London.

S.S. Mundeke

S.S. Mundeke, Kingston Upon Thames, UK

1st Generation British Born Congolese/Angolan, London.

Ma J.M. Kilapi

Ma J.M. Kilapi, D.R. Congo

1st Generation Congolese/Angolan, London

J. Mundeke

J. Mundeke, Kingston Upon Thames,

U.K. 1st Generation British born Congolese/Angolan, London

N. D-Nkufi

N. Diansunzuka-Nfuki Kingston Upon Thames,

UK 1st Generation British born Congolese, London

Vava Tampa

Founder of Save the Congo; Activist and Rhumba lover.

Tampa has been advocating for peace and justice in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 2008.

JJ Bola

Writer, Poet, Educator, Human.

Author of No Place to Call Home.

Spoken word poet turned author, Bola has read and spoken internationally at TedTalks and festivals.

Thomas Mukambilwa

Managing Director of African Support and Project Centre

Mukambilwa advocates for the improvement of Congolese lives in London through educational and health events