Collection

Theme

Country

Date

12 results

Alice Seeley Harris Archive

This archive of photographs was produced by the British missionary Alice Seeley Harris (1870-1970) during her time in the Congo Free State at the turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth century. Alice took over 1000 photographs depicting Congolese life, however, it is her images of the atrocities perpetrated in pursuit of rubber that have become internationally famous. These images were used by antislavery campaigners in Britain to raise awareness of the colonial violence which was used to force Congolese people to labour when the country was personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium during the period 1884-1908. Her photographs exposed the illusion that Leopold’s colony was founded on humanity and would ‘improve’ the lives of Congolese people. In Congo, as in other African colonies, European education, religion, technology, and medicine were all used as justification for the spread of colonisation. They also helped to mask, or make more palatable, the economic interests that drove European empire building including the theft of land, labour, and resources for profit. In contrast to Leopold's public statements about building a better future for Congolese people, Alice's images revealed the exploitation, domination, and brutality at the heart of the regime.

Alice's photographs should be understood in relation to both the history of the British empire and the racial thinking that underpinned it. Colonialism was based on ideas of European cultural superiority. Images of Africa produced by people from Europe often presented the continent’s rich and varied cultures as primitive, which produced new ways of seeing and valuing difference for European audiences. European colonisers used images and literature to depict African culture, religion, and society as unequal to their own – these kind of representations provided legitimacy for their claim that they had the right to rule others. The development of photography as a form of technology was in itself taken as a sign of the advancement of European peoples. Using this new technology to photograph the traditional ways of life in the colonies was a way of demonstrating European progress and modernity. By the late-nineteenth century, ethnographic photography became popular, it was a genre that represented colonial subjects as different; who could be categorised and ordered according to physical characteristics. These characteristics were then linked to ideas about intellectual capacity and morality, qualities many Europeans believed Africans lacked. For these reasons, despite Alice's antislavery activism, her photographs were not intended to represent Congolese people as equals. Instead they were designed to show people in Britain why they needed to intervene. This reinforced a sense of superiority for the British audience and confirmed their belief that the British empire was essentially a force for good. It is important to remember that although Britain was involved in antislavery in the Congo Free State, exploitative labour practices were common to all European empires and Britain was no exception.

Alice's photographs form part of an antislavery tradition in Britain that has spoken on behalf of enslaved people, rather than empowering them to speak for themselves. The images represent a European humanitarian mindset in which action must be taken on behalf of the passive victim whose helpless situation can only be addressed through appealing to a higher power, in this instance imperial Britain. What's more, this approach overlooks the responsibility colonizing powers had in creating the very conditions from which African people had to subsequently be saved from. Thus, Alice's photographs raise difficult questions about who has the power to represent, who has the power to bring about change, and who is denied this capacity both historically and in the present.

Guide for users

The photographs have been digitised along with their original captions. The original captions have been used to title each image. This is part of the work of preservation but the captions sometimes use language and concepts that are not in common parlance today. For example, half caste; although this language is offensive to modern audiences it is important to understand how viewers would have understood the image during the period, including the use of racial language to shape the meaning of the photograph. Search terms do not replicate this language.

You can search the images using geographic location. The original spelling of the place names contained within the caption have been used for the title of the image, however, some place names have changed their spelling over time e.g. Loanda; and Luanda. Tags have used the modern spelling of the place name. Items are tagged with place names from the period as well as the modern place name e.g. Leopoldville; and Kinshasa. You can search via Country - the place where the image was produced e.g. Angola.

The images have been tagged using generalised description of the individuals who feature in them e.g. African child; or European man. These terms are inadequate as they do not allow for the specificity that should be attributed to individual subjectivity, they also remove peoples' right to self-definition. The captions for the images do not contain the detailed information about the sitters which would allow for a greater degree of clarity. Judging a persons race or ethnicity based on a photograph risks wrongly attributing or imposing meaning, however, in order to make the archive searchable these terms have been used.

Each image has a zoom function will allows the viewer to examine the photograph in detail. If you click on the image you can navigate with the zoom to look at an individual's stance, expression, and other details. Humanitarian photography has employed techniques which have tended to erase the individual and present a suffering mass. The zoom function has been included so that viewers can engage with the people represented as individuals.

A selection of the photographs were used in the Congo Atrocity Lantern Lecture. Part of the glass slide collection owned by Antislavery International and housed at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford has been digitised by this project. You can search Related Items to view the lantern slides, or you can click through to the Congo Atrocity Lantern Lecture.

Both the original Alice Seeley Harris Archive and the Congo Atrocity Lantern Lecture represented African people through the colonial gaze. In replicating these archives we are very aware of the potential to reinstate that particular way of seeing difference. In order to make sure that this mode of representation is balanced by material which is self-representative we have commissioned two projects Decomposing the Colonial Gaze: Yole!Africa; and You Should Know Me: Photography and the Congolese Diaspora. You can search Alternative Tags, or you can click through to these collections to find new material which has been inspired by and critically engages with the historic archive.

The project has also collaborated closely with the Antislavery Knowledge Network, which is based at the University of Liverpool, and seeks community-led strategies for creative and heritage-based interventions in sub-Saharan Africa.

Copyright and takedown policy

Copyrights to all resources are retained by Antislavery International, who have kindly made their collections available for educational and non-commercial use only. All efforts have been made to obtain copyright permission for materials featured on this site. If you are aware of instances where the rights holder(s) has not been given an appropriate credit, please let us know. If you hold the rights to any item(s) included in this resource and oppose to its use, please contact us to request its removal from the website.

Email: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

This archive would not have been possible without the generous access given to the project by Antislavery International. In particular we would like to thank Dr Aidan McQuade and Dr Anna Shepherd. The digitisation was completed by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Archivist Lucy McCann gave invaluable help with locating the full archive. We would like to thank Nick Cistone and Linda Townsend for their assistance with this process. Mike Gardner at the University of Nottingham has lent his technical support throughout the project. Discussions about this project were greatly enhanced by conversations with Dr Mark Sealy (Director, Autograph ABP) and Dr Richard Benjamin (International Slavery Museum). Congolese artist Sammy Baloji offered unique insights into the relationship between past and present forms of representation. This project was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. Further thanks go to the Antislavery Knowledge Network, based at the University of Liverpool.

Further reading

Marouf Hasian Jr., Alice Seeley Harris, the atrocity rhetoric of the Congo Reform Movements, and the demise of King Leopold's Congo Free State, Atlantic Journal of Communication, 23:3, (2015), pp. 178-92

Kevin Grant, 'Christian critics of empire: Missionaries, lantern lectures, and the Congo reform campaign in Britain', Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 29:2, (2001), pp. 27-58

Kevin Grant, 'The limits of exposure: Atrocity photographs in the Congo reform campaign', in Fehrenbach, Heide and Rodogno, Davide (eds), Humanitarian photography: A history, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015) pp. 64-88

Fuyuki Kurasawa, The sentimentalist paradox: On the normative and visual foundations of humanitarianism, Journal of Global Ethics, 9:2 (2013), pp. 201-14

John Peffer, 'Snap of the whip / Crossroads of shame: Flogging, photography, and the representation of atrocity in the Congo Reform campaign, Visual Anthropology Review, 24:1 (2008), pp. 55-77

Christina Twomey, 'Framing atrocity: Photography and humanitarianism,' History of Photography, 36:3 (2012), pp. 255-64

Mark Sealy, "http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11794/1/Sealy_Revised_Phd_Decolonizing_the_Camera-_Photography_in_Racial_Time__.pdf' Decolonising the camera: Photography in racial time' (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Durham, 2016)

Sharon Sliwinski, The childhood of human rights: The Kodak on the Congo, Journal of Visual Culture, 5:3 (2006), pp. 333 - 363

Sharon Sliwinski, 'The childhood of human rights: The Kodak on the Congo, Journal of Visual Culture, 5:3 (2006), pp. 333 - 63

Links

http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ism/exhibitions/brutal-exposure/alice-seeley-harris.aspx" Brutal Exposure at the International Slavery Museum.

https://soundcloud.com/autographabp/alice-seeley-harris-interview" Interview with Alice Seeley Harris

https://autograph.org.uk/exhibitions/congo-dialogues" Congo Dialogues: Alice Seeley Harris and Sammy Baloji, Autograph ABP

T. Jack Thompson, http://www.internationalbulletin.org/issues/2002-04/2002-04-146-thompson.pdf" Light on the dark continent: The photography of Alice Seeley Harris and the Congo atrocities of the early twentieth century https://olijacobsen.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/missionary-campaigns-and-atrocity-photographs.pdf

Daniel J. Danielsen and the Congo: Missionary campaigns and atrocity photographs (Brethren Archivists and Historians Network, 2014)

https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/politics/research/research-projects/akn/">Antislavery Knowledge Network, University of Liverpool

Tree ferns, Ikelemba forest

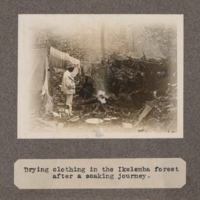

Drying clothing on the Ikelemba forest after a soaking journey

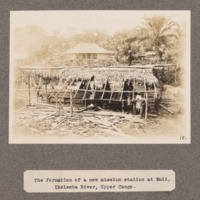

The formation of a new mission station at Euli, Ikelemba River, upper Congo

Cotton growing on the Ikelemba

Tree ferns on the Ikelemba

A difficult tramp through the Ikelemba – Juapa watershed

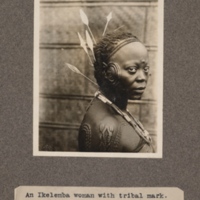

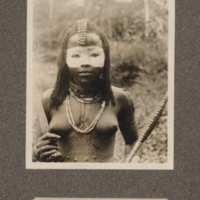

An Ikelemba woman with tribal mark

Chief on the Ikelemba

Witch at Euli, Ikelemba

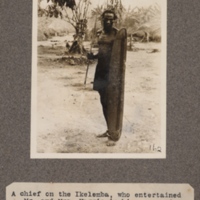

A chief on the Ikelemba, who entertained Mr. and Mrs. Harris in his compound

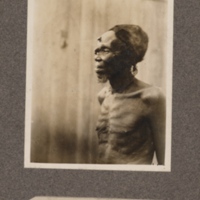

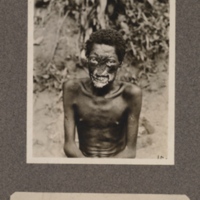

Leper at Euli, Ikelemba River, upper Congo